Upon his recent death, Dr. Harold Bailey has been universally praised by civic leaders including our current Mayor and Governor. Mayor Keller states: “He was a champion of so many endeavors that have enriched our city, state and our nation, from African American studies, to civil rights, to childhood development.” Governor Lujan Grisham notes that “Under Dr. Bailey’s leadership, the Albuquerque NAACP endorsed the Elizabeth Whitefield End of Life Option Act in 2020, championing expanded healthcare options and addressing disparities in education and access.”

Impressive, but missing in the kind words of Keller, Lujan Grisham and others in charge now is the extremely important fact that such praise was not always extended by leaders “back in the day.”

Oh, no. Not even.

And it is Dr. Bailey’s leadership, perseverance and success despite widespread civic unpopularity that better documents how great this man was.

So let’s look back into a few among his many noteworthy run-ins with the powers that were.

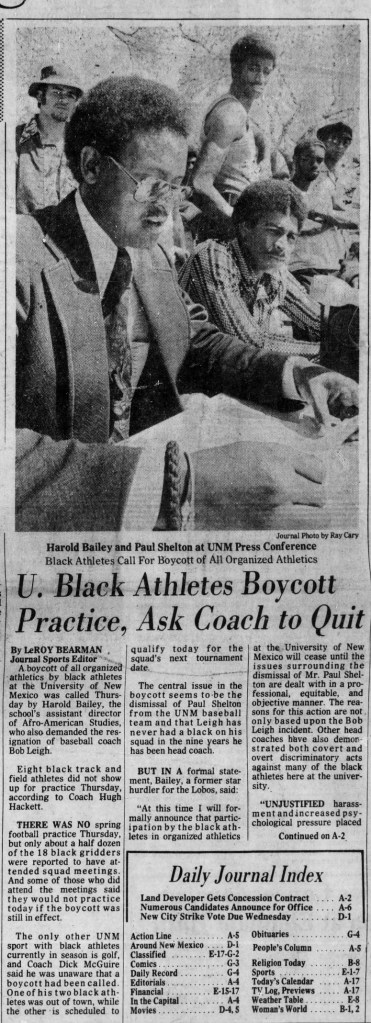

Back in 1974, Harold was UNM’s Assistant Director of Afro-American Studies while working on his Ph.D. at the school. He’d heard unsettling reports of discrimination from several UNM scholar/athletes, including recently dismissed baseball player Paul Shelton.

Just about everybody working on their Ph.D. would hear such reports and keep their mouth shut until they got their Doctorate. Especially when it involved that hallowed institution: sports. Especially, especially given Harold had himself been a track star at the University. Heck, pretty much everybody would keep that mouth good and shut right up until they achieved tenure, if need be.

Not Harold. Instead of keeping his mouth shut, Doctorate-aspirant Bailey coordinated a boycott of all UNM athletic programs.

As you might imagine, even today, coordinating a boycott of athletic programs was not the most popular idea in town. For instance, here’s the reaction of boycotted UNM Baseball Coach Bob Leigh:

To help readers squinting at the above, Coach Leigh is quoted as saying, “And if anybody ought to be fired or resign it ought to be Harold Bailey and not myself.” Tribune reporter “Unnamed” (note the lack of a byline…hmmm) also includes observations of University of Arizona baseball coach Jerry Kindall to support Coach Leigh’s position.

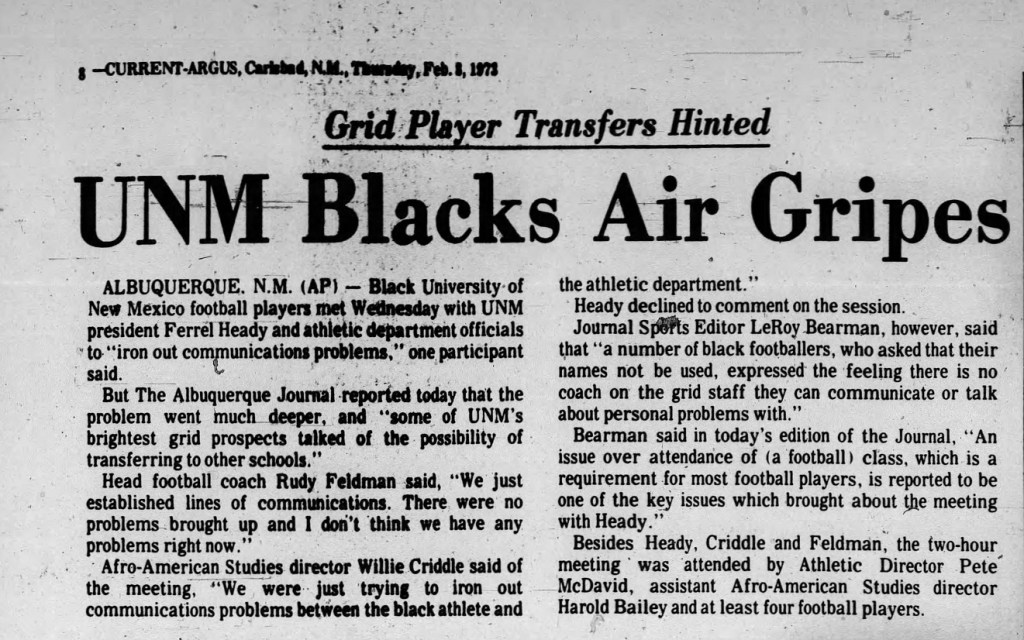

By the time of the 1974 boycott, Harold’s work in giving public voice to UNM athlete concerns had already been in place for some time. Here’s an Associated Press story printed in the Carlsbad Current Argus over a year earlier on February 8, 1973.

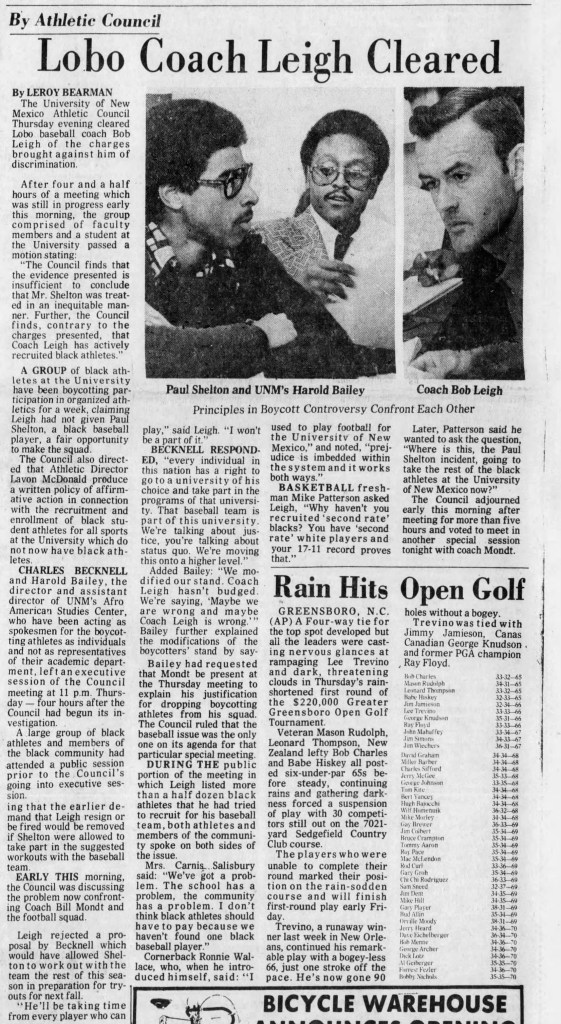

In the case of the 1974 boycott, which successfully spread to many sports, Albuquerque papers were keen to publish defenses of Coach Leigh such as this:

And the University’s good ‘ol boy “Athletic Council” “cleared” Coach Leigh from blame, despite continued concerns voiced by Bailey and others.

On April 7, 1974 , the day fittingly before Henry Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record, the UNM athletic boycott ended:

At that point, things seem to settle down and everybody got back to the hallowed institution of sportsball. But as with all great work, Dr. Bailey’s efforts took a while, and significant opposition, to bear fruit. A month or so later, the Journal published the following story, interestingly written not by a local reporter, but by UPI’s Pete Herrera.

Included above is mention that UNM Athletic Director Lavon McDonald “now has indicated a change may soon be in order” regarding Leigh’s tenure as baseball coach, adding “he has come in for criticism from McDonald for not recruiting more New Mexico players.”

Leigh professionally survived for a while, and the local papers offered him space to defend himself and his program throughout Summer. But by late October of ’74 he was out.

Leigh’s firing was blamed in part on the coach’s refusal to take on extra duties without a raise, and other red herrings, but Dr. Harold Bailey’s work, though either unmentioned or dismissed as unimportant in the press, was essential in bringing the issues to the forefront and in starting to change a discriminatory institution.

Not many folks back in 1974 would agree with that assessment of the outcome. Heck, there’s probably plenty of folks, or at least a few, still around today who recall the sports boycott and still think Harold was a troublemaker and wrong. I imagine a great many first hearing/reading of the boycott these days would be: A. shocked; B. outraged if anybody tried to boycott our precious college athletics today.

And that’s precisely why it’s important to go back and visit Dr. Harold Bailey’s accomplishments in context of the time in which he did the work. Having the Mayor and Governor praise Bailey in death is one thing, but taking the time to understand why one is worthy today of such praise despite being widely attacked and unpopular while living is another.